Social injustice or economic inequality?

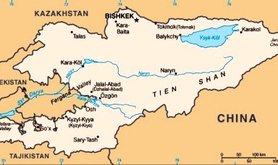

How can we explain the April 2010 uprising in Bishkek and the June 2010 clashes in Osh? One is a political event, and the other relates to ‘ethnic violence’; one we celebrate, and the other we condemn. But both relate to underlying economic inequalities. While social scientists are quick to point out social injustices (such as ethnic and gender discrimination) and violations of civil and human rights (especially media and religious freedoms), class hurt, injuries, discrimination and suffering are not often treated as an injustice or as a violation to human dignity. Without proper attention to economic disparities and class distortions of human evaluations, relationships and practices, any attempts at reconciliation or moral healing between ethnic groups are likely to flounder.

Economic inequality is significant in explaining sporadic looting, land grabbing and inter-ethnic conflicts in the country. Urban middle class residents view most rural migrants with contempt and disdain, calling the ruralised urban poor myrkas (uncultivated and uneducated). The poor migrants in turn feel humiliated and angry, but some young men counter the negative feelings with an exaggerated sense of masculinity and nationalism.

Rural ethnic majority Kyrgyzs have periodically targeted affluent urban and suburban ethnic minority groups (such as Uyghurs, Dungans, Meskhetian Turks, Uzbeks and Slavic Russians) for abuse and assault, in particular, erupting into land grabs and ethnic violence. For instance, after a wave of land grabs that followed the change in power in the March 2005, the so-called ‘Tulip Revolution’, ethnic Meskhetian Turks in the Novopavlovka village, found leaflets on their doors that said, ‘Down with Turks, go away from our land. We will burn you if you hesitate.’

During the power vacuum that followed the fall of then President Akayev, many ethnic Slavic Russian businesses were also targeted by looters. In February 2006, a violent clash between ethnic Dungans and young ethnic Kyrgyzs erupted in the village of Iskra. At the time, an ethnic Kyrgyz in Iskra expressed his negative sentiments against the ethnic minority group, ‘Dungan families have always been better off. Their children, when fighting or arguing with their Kyrgyz peers, used to tease them that they are mainly poor. Many Kyrgyz work the fields belonging to Dungan people who are sometimes viewed as outsiders, so this resentment is growing further.’

Bishkek

Following the 7 April 2010 uprising in Bishkek, slum dwellers and poor groups began to loot major shopping malls and stores, which led the middle classes to establish ‘people’s militias’ to patrol the streets. Almost two weeks later, there was a riot in the village Mayevka, in the suburbs of Bishkek. Initially, the mass media framed the riot as an ‘inter-ethnic conflict’ clash between ethnic Kyrgyzs and ethnic Meskhetian Turks. But it is more accurate to suggest that, after the interim government had denied their claim for land plots, poor Kyrgyzs living in novostroyki (new housing estates) sought to grab land from the Meskhetian Turks. The riot on 19 April 2010 was an issue about land, not ethnicity per se. While access to land had became ethnicised and politicised in this particular incident, slum dwellers in Bishkek largely justify their claims to land on moral grounds.

Osh

I suggest that the ethnic violence in Osh that started on 11 June also relates to economic inequalities. Neo-liberal market and agricultural reforms have proved to be a disaster for Kyrgyzstan, causing rural poverty and labour migration to Bishkek and Osh. As a result, illegal settlements have developed on the outskirts of these cities. Bishkek has 47 novostroyki, and Osh has eight. Houses in novostroyki often lack basic necessities, such as sanitation, running water and electricity. As in Novopavlovka, Iskra and Mayevka, ethnicity does not operate in a social vacuum: people’s everyday identities are shaped by other social structures, such as class, gender and age. Understanding the nature of ethnicity requires a careful examination of how various key factors came together in a particular set of conditions, which resulted in an immediate and widespread explosion of violence in the city. While no single factor can adequately explain the events, class inequalities require special attention, and in reconstructing the events with a focus on class relationships, I do not wish to deny the importance of ethnicity, gender and political elites.

Kyrgyz vs Uzbek in Osh

In their desire to seek economic redress, many rural residents and some living in novostroyki looted and burnt shops, cafes and businesses belonging to the dominant urban middle class Uzbek community. Their anger, envy and frustration particularly focused on looting and destroying Uzbek business property and private homes. Having not gained from the trickle-down effect of the previous economic growth periods and being impoverished by the market system, they saw no reason to respect others’ wealth and property. They were intent on destroying the wealth and symbols of the urban petite bourgeoisie. Following the initial unrest on 11 June, looters stole from the large Osh Bazaar, and then burnt it down, leaving both Uzbek and Kyrgyz businesses destroyed. Even kiosks spray-painted with the word ‘Kyrgyz’, which throughout the city had offered some protection to homes and business from Kyrgyz youth gangs, were not spared. Economic redress, not ethnic hatred, appears to be the driving force behind the destruction. In Bishkek, following the events in Osh, poor Kyrgyzs made threats against the Uyghur business community, causing many Uyghurs to leave Bishkek temporarily to stay with relatives and friends in Astana, Kazakhstan.

There were horrific and gendered elements to the violence unleashed in Osh. While some commentators have attributed the Kyrgyz sentiments of resentment, anger and hatred towards the Uzbek to ethnicity, these emotions can be better explained as a reaction of poor people’s own feelings of humiliation, shame and inferiority. The poor Kyrgyzs also reacted to the growing self-confidence and pride of the affluent urban Uzbek middle class in Osh, which started to demand greater language rights and better access to high-ranking political and civil service positions. The Uzbek petite bourgeoisie were no longer content with the existing social status quo and the division of societal roles which meant that the Uzbeks primarily performed an economic function, and the Kyrgyzs occupied top-level political and military positions. Buoyed by significant wealth, the Uzbek urban community demanded a greater recognition of their political and social rights, which angered and scared both the Kyrgyz elites and poor groups. It is in this complex and emotional context that many young and poor rural Kyrgyz men were inflamed to feeling aggressive, masculine, proud and nationalistic, so that sexual violence against Uzbek women and girls became enmeshed with the destruction of Uzbek private property.

While investigations have started to ascertain which leaders and groups instigated the tragic Osh events, it is clear that they were able to tap into powerful collective sentiments of class hurt and confidence, ethnic hatred and pride, aggressive masculinity and communal anxieties that had swelled up over the years between affluent urban Uzbek people and poor rural Kyrgyz residents. Poor rural men and slum dwellers living on the margins of Osh city had little reason to respect Uzbek people and property, and the scale of violence is a witness to the pent-up rage waiting to be unleashed. In many ways it is hardly surprising that highly symbolic and visual sites, such as the famous Osh Bazaar and several Uzbek ethnic enclaves, were attacked. While dressing up their grievances in terms of historical ethnic rivalry, the narrative of the poor rural class reflects a common strategy of destruction and mass violence in the face of humiliation and class injury. Consumed with excessive anger, rage and hatred, poor rural Kyrgyzs were unable to have any sympathy for others or to act with practical reason. Not that there can be any justification for the widespread and intense level of violence that transpired: individuals are ultimately responsible for their own actions.

Bishkek: justifying the violence

In order to ascertain key regional differences, it is fruitful to compare how rural migrants and poor Kyrgyz groups in Osh and Bishkek responded to economic inequalities. In Bishkek, poor migrants and groups have five important moral justifications for taking land and goods that constitutes their understanding of the moral economy of land. First, their moral rights to basic goods and land draw upon the old moral system of the Soviet welfare state and what it means to be a human being – it is difficult to imagine being truly human without space and basic goods. Land is fundamental to existence, since without it we could not sleep, rest, socialise or wash ourselves.

Second, urbanised rural poor groups have little reason to respect the rights of the property-owning class, when their own human rights have been grossly violated. People without registration documents living in Bishkek novostroyki have limited access to education, health, social benefits and formal political participation, live under a threat of eviction, and are despised as myrkas by most ‘respectable’ middle class Bishkekers. The rich property-owning class rules without responsibilities, and the poor property-less class lives without rights.

Third, Bishkek slum dwellers argue that if the then President Bakiyev’s family and elites were looting and grabbing national assets, and improperly acquired the wealth to finance their lavish and wasteful lifestyles, then it is reasonable for the slum dwellers to grab plots of land to make ends meet. They feel that it is unfair and unjust that the ‘untouchable’ class can evade the law, while they have to stay within legal structures.

Fourth, they also legitimise their seizures on the basis of the land code and government promises. They feel that they are entitled to plots of land under the law, though there are conflicting legal interpretations. Fifth, land invaders note the irony of the interim leaders, who grabbed power claiming moral legitimacy, but then asserted that the slum dwellers’ grabbing of land was illegal, despite their moral claims and need. If the interim government grabbed power, then the homeless can grab land.

Osh: powerless authorities

In contrast, the powers of the interim government, the local police, the military and local voluntary security brigades were very limited in constraining rural migrants and poor groups in southern Kyrgyzstan. The state, weakened by a decade or so of neo-liberal market reforms against the welfare state, was powerless to prevent poor migrants and groups destroying economic wealth and evicting the affluent Uzbek business community. It is in the context of fragile state-society relations that the politics of envy and anxiety of Kyrgyz rural residents and slum dwellers in novostroyki combined with the politics of cultural recognition of affluent Uzbek mahallas (urban divisions) to produce intense tensions and conflicts. Violence was almost inevitable.

Reconciliation in Osh will be difficult when images and reports in the mainstream media, social networking sites and blogospheres frame the Osh events as an inter-ethnic conflict. Rather than informing, they inflame further distrust and incriminations of wrongdoings on both sides, pitting ‘Kyrgyzs’ against ‘Uzbeks’.

The way forward

Looking into the future, we require a process of moral repair and healing in the country that tackles deep collective emotional hurt, recognition of equal dignity, communal mistrust and a lack of fulfilment of normative expectations of state support and security. The process of moral repair cannot be simply discursive or symbolic. It has to involve real and material changes to how society distributes resources and wealth, otherwise moral aspirations will fail to match the economic reality. Forgiveness and reconciliation require real recognition of wrongdoing and hurt, and people need to take responsibilities for their actions, rather than blaming others (the Bakiyev family, radical Islamic groups or ‘third forces’). But forgiveness and recognition is unlikely to develop in the context of social and spatial inequalities that prevent people being sympathetic towards others, evaluating others as unworthy of respect, dignity, equality and recognition. Structural inequalities tend to demonise, marginalise and characterise others as inferior or superior on the basis of their economic standing. Class equality matters because it facilitates a genuine recognition that others (whether they are Uzbeks or Kyrgyzs, men or women, young or old) deserve to be equally treated as human beings, being sympathetic to their vulnerabilities and needs. Without economic re-distribution and greater equalities, the process of moral repair and healing is likely to be meaningless and fruitless.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.